Memory Management

Overview

- Background

- Demand Paging

- Process Creation

- Page Replacement

- Allocation of Frames

- Thrashing

- Operating System Examples

Background

Why we don’t want to run a program that is entirely in memory

- Many code for handling unusual errors or conditions

- Certain program routines or features are rarely used

- The same library code used by many programs

- Arrays, lists and tables allocated but not used

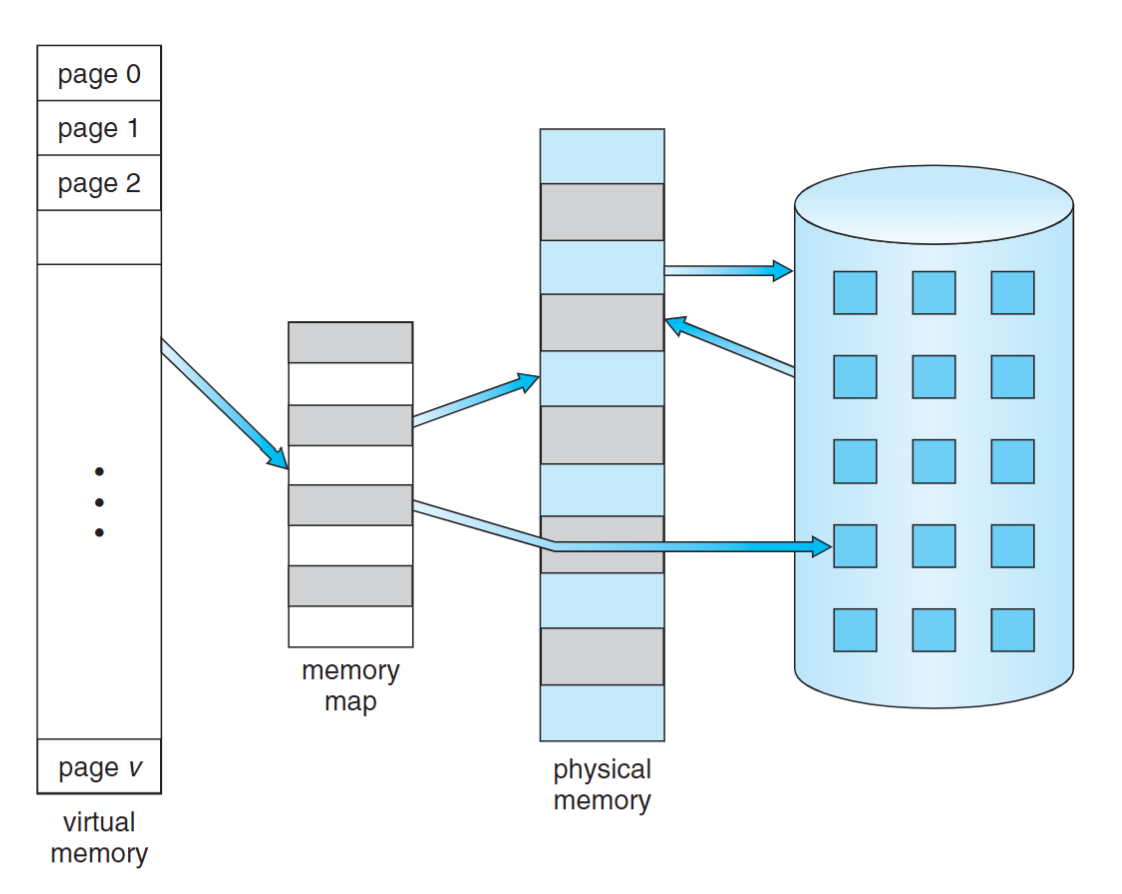

Virtual memory: separation of user logical memory from physical memory

- To run a extremely large process: Logical address space can be much larger than physical address space

- To increase CPU/resources utilization: higher degree of multiprogramming degree

- To simplify programming tasks: Free programmer from memory limitation

- To run programs faster: less I/O would be needed to load or swap

Virtual memory can be implemented via

- Demand paging (most common)

- Demand segmentation: more complicated due to variable sizes

Demand Paging

- A page rather than the whole process is brought into memory only when it is needed

- Less I/O needed -> Faster response

- Less memory needed -> More users

- Page is needed when there is a reference to the page

- Invalid reference -> abort

- Not-in-memory -> bring to memory via paging

- pure demand paging

- Start a process with no page

- Never bring a page into memory until it is required

Notice that a swapper (midterm scheduler) manipulates the entire process, whereas a pager is concerned with the individual pages of a process.

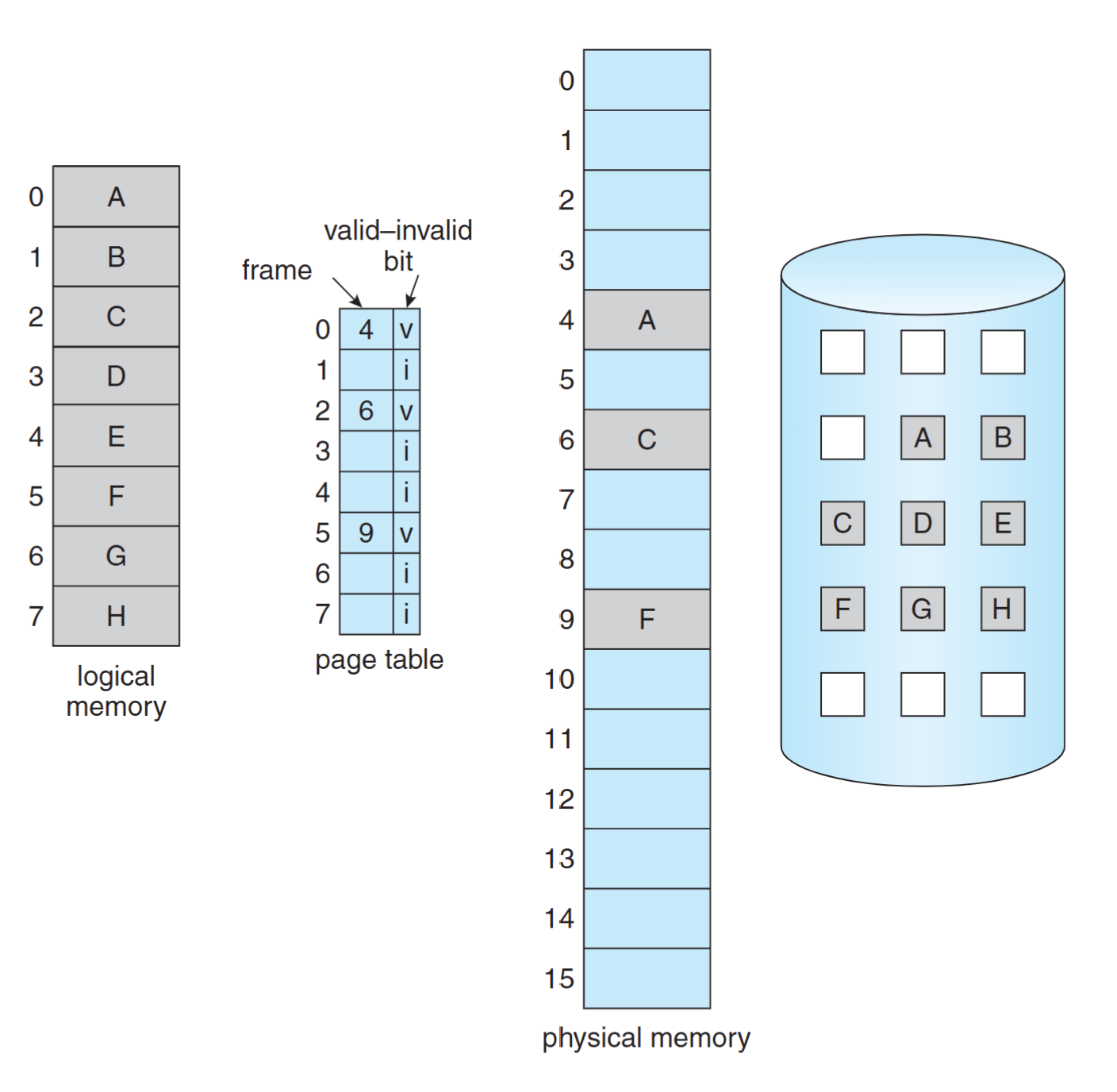

Hardware support

- Page Table: a vlid-invalid bit

- 1: page is in memory

- 0: page is not in memory

- initially all bits are set to 0

Page table when some pages are not in main memory

Page table when some pages are not in main memory

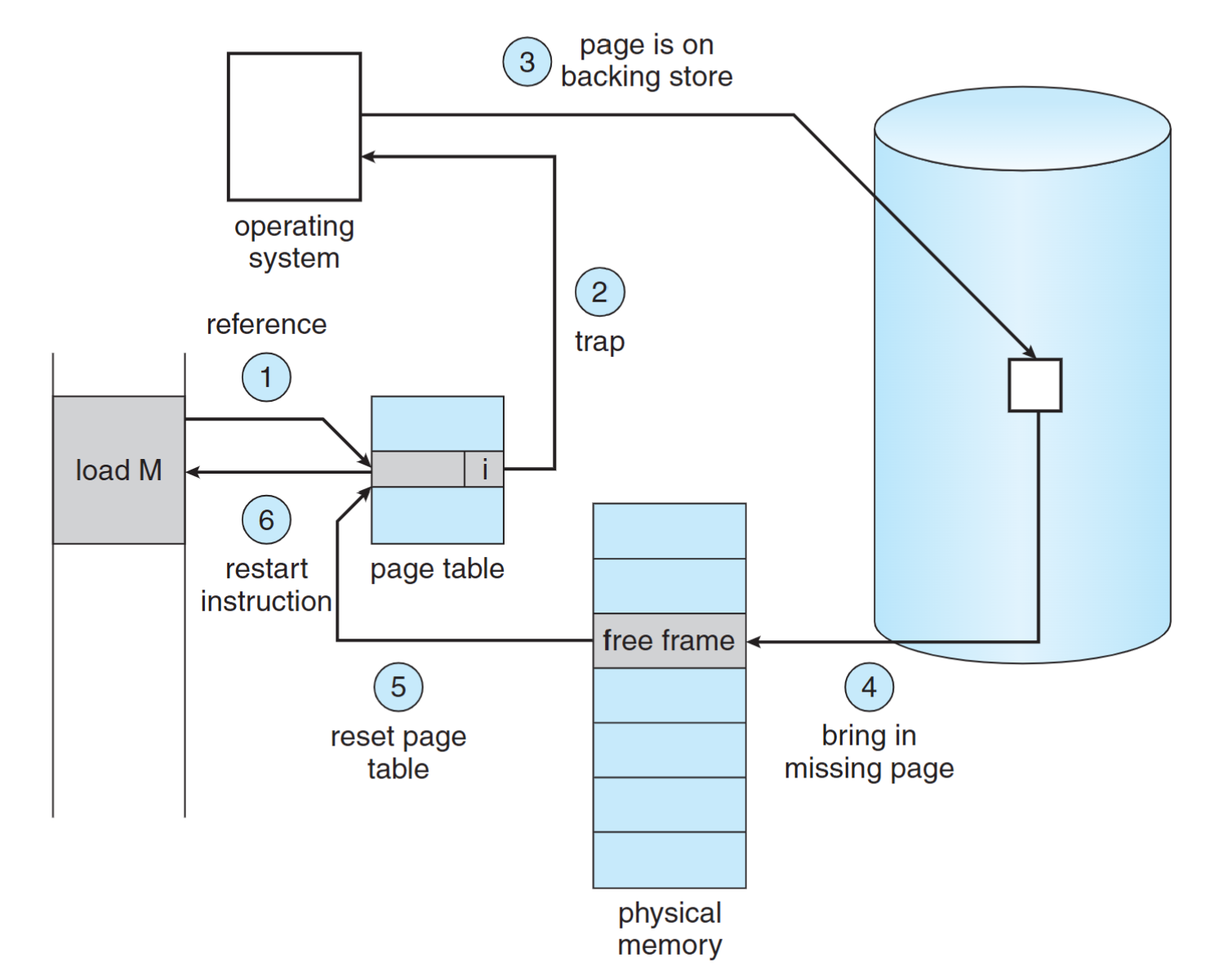

Page Fault

First reference to a page will trap to OS: page-fault trap

OS looks at the internal table (in PCB) to decide

- Invalid reference -> abort

- Just not in memory -> continue

Get an empty frame

Swap the page from disk (swap space) into the frame

Reset page table, valid-invalid bit = 1

Restart instruction

Steps in handling a page fault

Steps in handling a page fault

Page Replacement

If there is no free frame when a page fault occurs

- Swap a frame to backing store

- Swap a page from backing store into the frame

- Different page replacement algorithms pick different frames for replacement

Demand Paging Performance

Effective Access Time (EAT): (1 – p) x ma + p x pft

- p: page fault rate, ma: mem. access time, pft: page fault time

Example: ma = 200ns, pft = 8ms

- EAT = (1 - p) x 200 ns + p x 8m = 200ns + 7,999,800 ns x p

- Access time is proportional to the page fault rate

- If one access out of 1,000 causes a page fault, then EAT = 8.2 microseconds. -> slowdown by a factor of 40

- For degradation less then 10%: 220 > 200+ 7,999,800 × p, p < 0.0000025 -> one access out of 399,990 to page fault

Programs tend to have locality of reference

- Locality means program often accesses memory addresses that are close together

- A single page fault can bring in 4KB memory content

- Greatly reduce the occurrence of page fault

Major components of page fault time (about 8 ms)

- serve the page-fault interrupt

- read in the page from disk (most expensive)

- restart the process

The 1st and 3rd can be reduced to several hundred instructions. The page switch time is close to 8ms. (There are more detailed steps in the book)

Process Creation

- Demand Paging: only bring in the page containing the first instruction

- Copy-on-Write: the parent and the child process share the same frames initially, and frame-copy when a page is written

- Memory-Mapped Files: map a file into the virtual address space to bypass file system calls (e.g.,

read(), write())

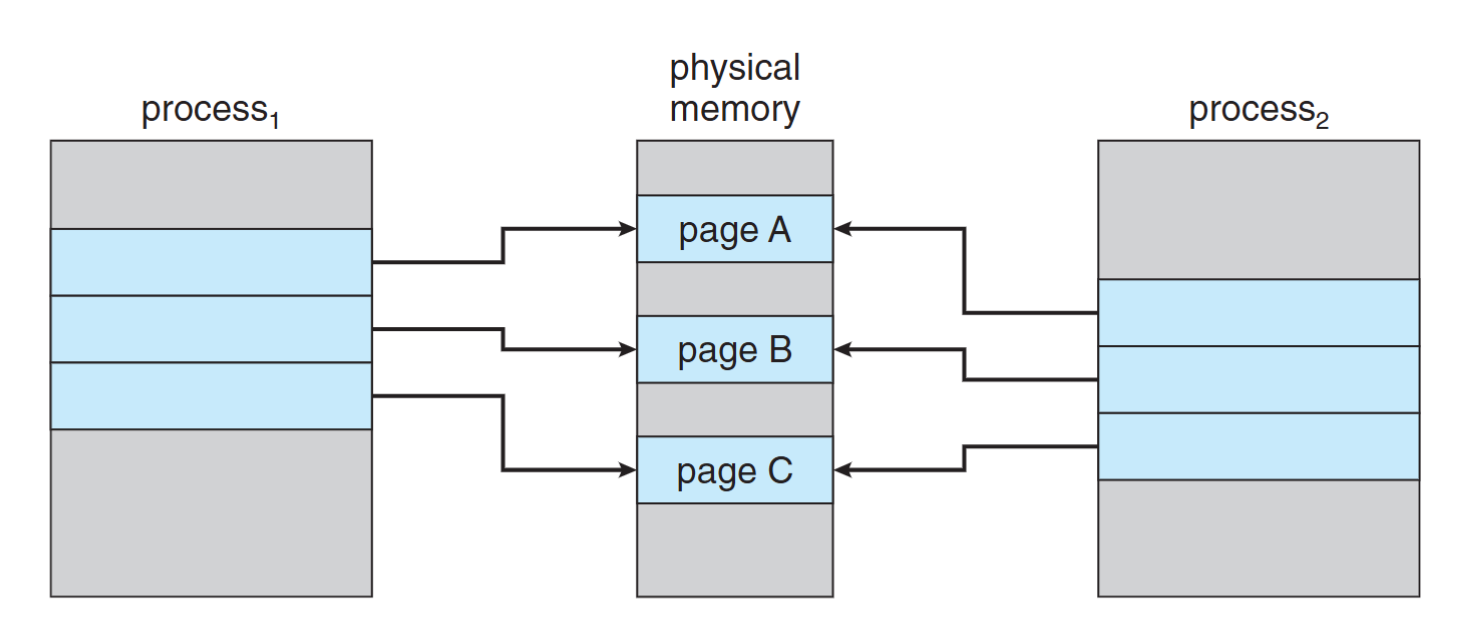

Copy-on-Write

Allow both the parent and the child process to share the same frames in memory

- If either process modifies a frame, only then a frame is copied

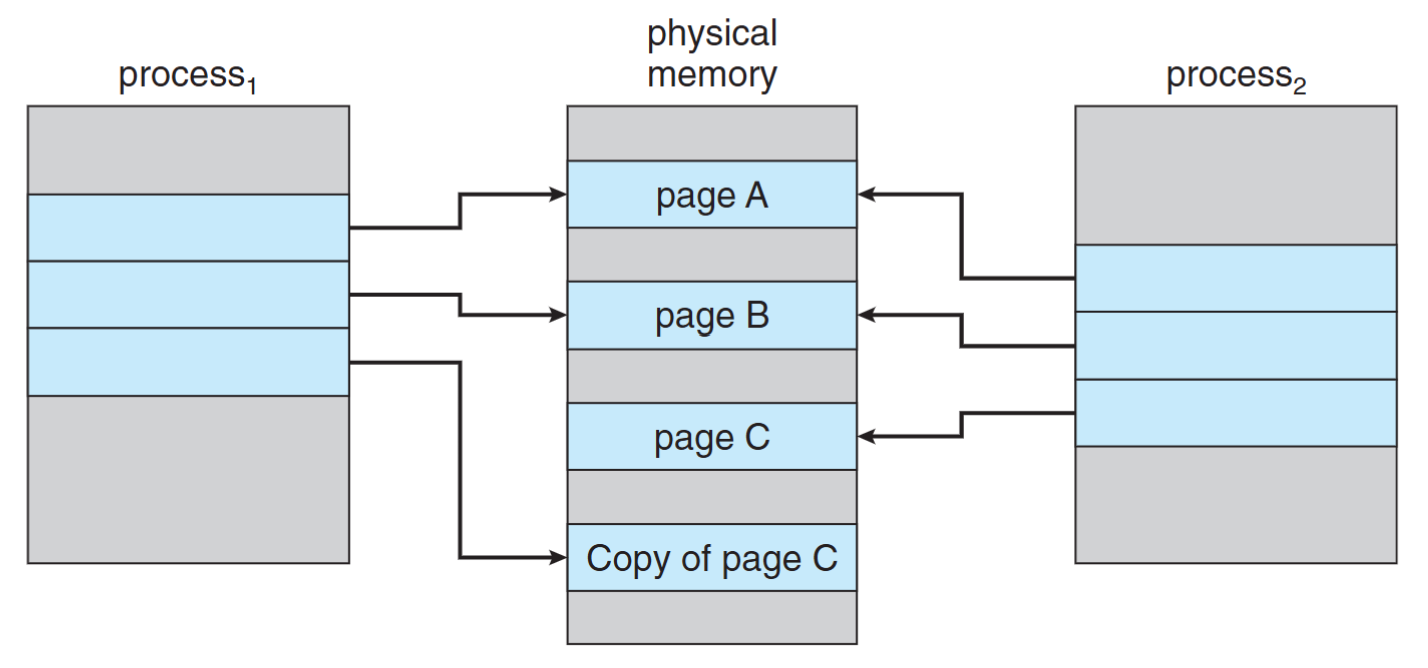

- COW allows efficient process creation (e.g.,

fork()) - Free frames are allocated from a pool of zeroed-out frames (security reason)

- The content of a frame is erased to 0

Before process 1 modifies page C

Before process 1 modifies page C

After process 1 modifies page C

After process 1 modifies page C

Memory-Mapped Files

Approach:

- MMF allows file I/O to be treated as routine memory access by mapping a disk block to a memory frame

- A file is initially read using demand paging. Subsequent reads/writes to/from the file are treated as ordinary memory accesses

Benefit:

- Faster file access by using memory access rather than read() and write() system calls

- Allows several processes to map the SAME file allowing the pages in memory to be SHARED

Concerns: Security, data lost, more programming efforts

Page Replacement

When a page fault occurs with no free frame

- swap out a process, freeing all its frames, or

- page replacement: find one not currently used and free it

- Use dirty bit to reduce overhead of page transfers – only modified pages are written to disk

Solve two major problems for demand paging

- frame-allocation algorithm: Determine how many frames to be allocated to a process

- page-replacement algorithm: select which frame to be replaced

Page Replacement Algorithms

Goal: lowest page-fault rate

Evaluation: running against a string of memory references (reference string) and computing the number of page faults

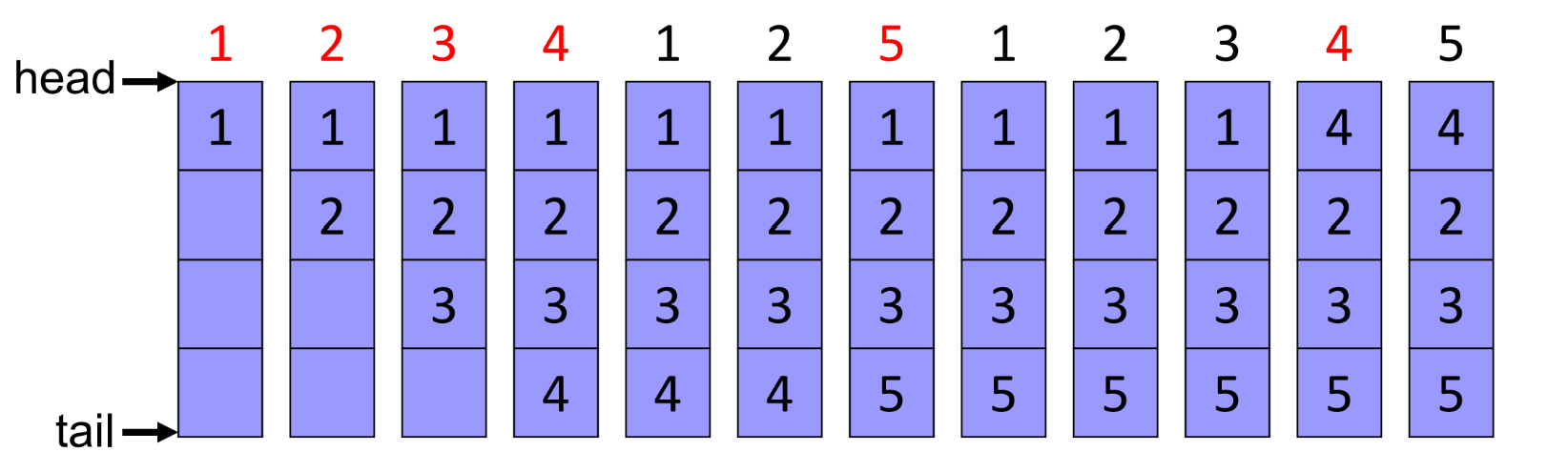

Reference string: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

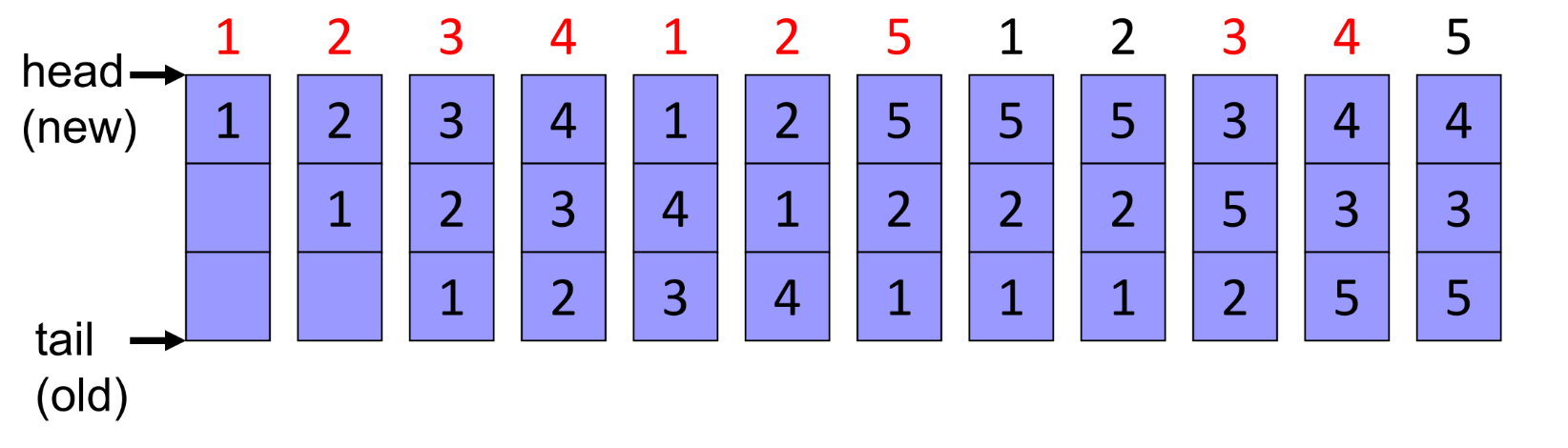

FIFO algorithm

Optimal algorithm

LRU algorithm

Counting algorithm

- LFU

- MFU

FIFO Algorithm

The oldest page in a FIFO queue is replaced

- Reference string: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

- 3 frames (available memory frames = 3) -> 9 page faults

a red number means that we have a page fault

a red number means that we have a page fault

Does more allocated frames guarantee less page fault?

- Reference string: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

- 4 frames (available memory frames = 4) -> 10 page faults!

Belady’s anomaly: the page-fault rate may increase as the number of allocated frames increase

Optimal algorithm

Replace the page that will not be used for the longest period of time, however, such an algorithm does exist, since we need to know the future reference string

- 4 frames: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 -> 6 page faults

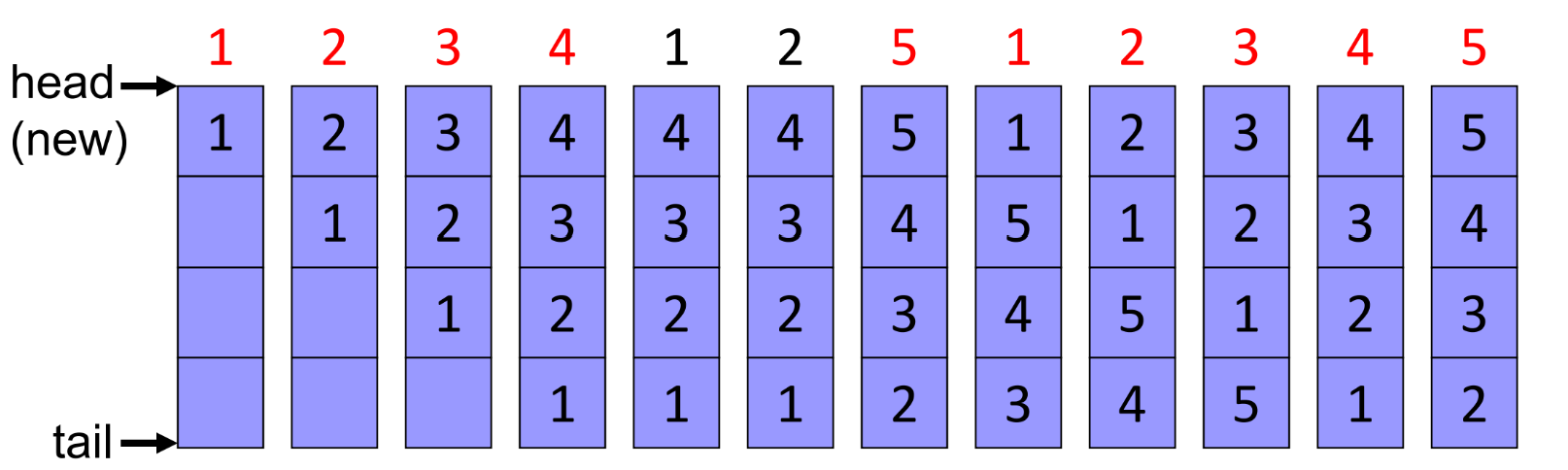

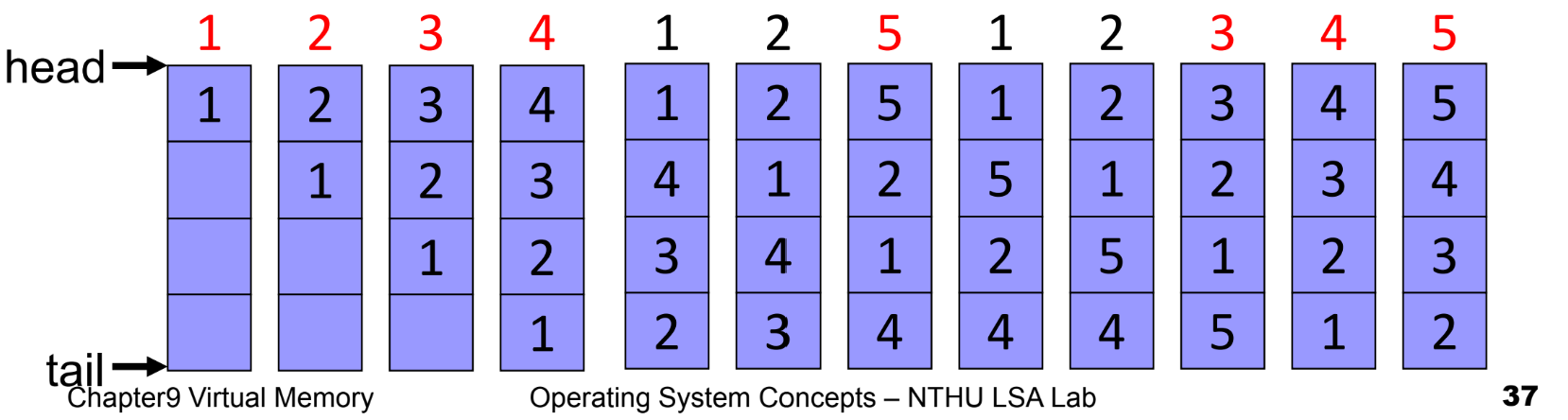

LRU algorithm

An approximation of optimal algorithm:

- looking backward, rather than forward

- It replaces the page that has not been used for the longest period of time

- It is often used, and is considered as quite good

Counter implementation

- page referenced: time stamp is copied into the counter

- replacement: remove the one with oldest counter, but linear search is required

Stack implementation

- page referenced: move to top of the double-linked list

- replacement: remove the page at the bottom

- 4 frames: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 -> 8 page faults!

Stack Algorithm

- A property of algorithms

- Stack algorithm: the set of pages in memory for n frames is always a subset of the set of pages that would be in memory with n + 1 frames

- Stack algorithms do not suffers from Belady’s anomaly

- Both optimal algorithm and LRU algorithm are stack algorithm

LRU approximation algorithms

Few systems provide sufficient hardware support for the LRU page-replacement (the textbook has a detailed introduction)

- additional-reference-bits algorithm

- second-chance algorithm

- enhanced second-chance algorithm

Counting Algorithms

LFU Algorithm (least frequently used)

- keep a counter for each page

- Idea: An actively used page should have a large reference count

MFU Algorithm (most frequently used)

- Idea: The page with the smallest count was probably just brought in and has yet to be used

Both counting algorithm are not common

- implementation is expensive

- do not approximate OPT algorithm very well

Allocation of Frames

Introduction

- Each process needs minimum number of frames

- The minimum number of frames is defined by the computer architecture

- e.g.: IBM 370 – 6 pages to handle Storage to Storage MOVE instruction:

- the instruction is from storage location to storage location, it takes 6 bytes and can straddle two pages

- Moving content could across 2 pages

Fixed allocation

- Equal allocation: 100 frames, 5 processes -> 20 frames/process

- Proportional allocation: Allocate according to the size of the process

Priority allocation

- using proportional allocation based on priority, instead of size

- if process P generates a page fault

- select for replacement one of its frames

- select for replacement from a process with lower priority

Global versus Local Allocation

- Local allocation: each process select from its own set of allocated frames

- Global allocation: process selects a replacement frame from the set of all frames

- one process can take away a frame of another process

- e.g., allow a high-priority process to take frames from a low-priority process

- good system performance and thus is common used

- A minimum number of frames must be maintained for each process to prevent trashing

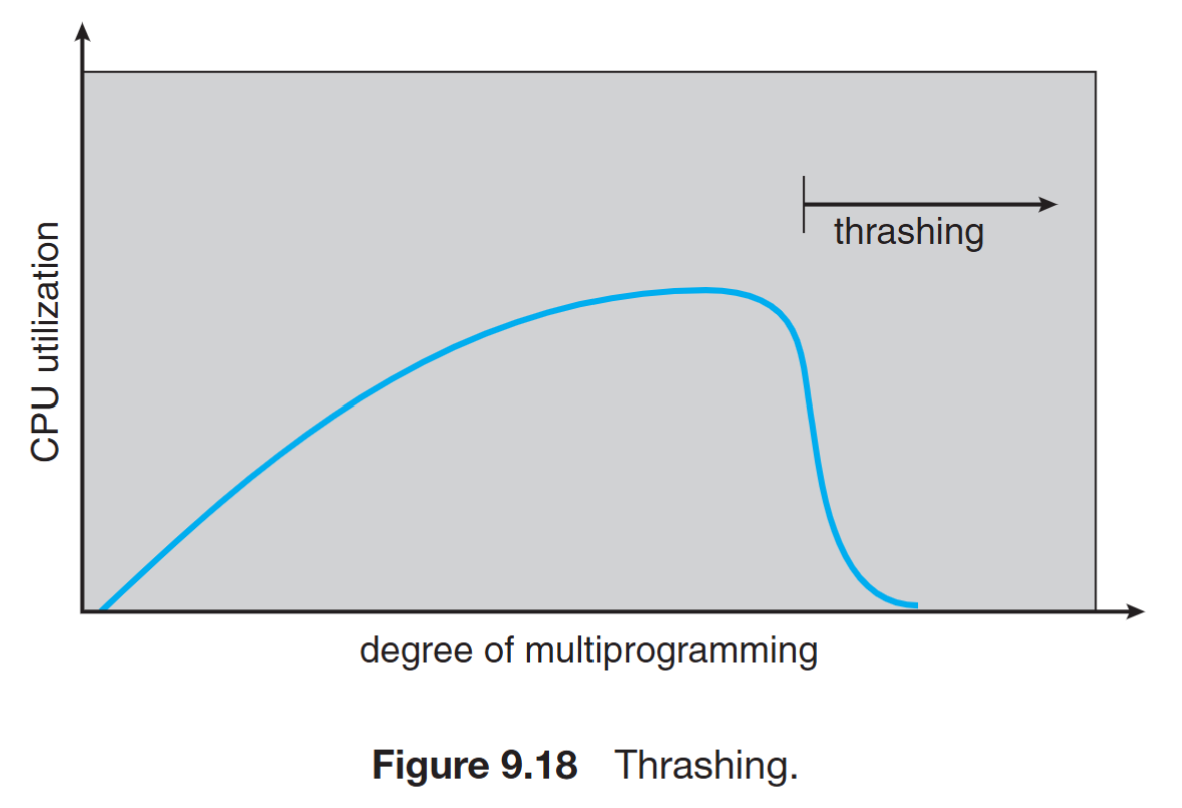

Thrashing

- If a process does not have “enough” frames, the process does not have # frames it needs to support pages in active use

- Very high paging activity

- A process is thrashing if it is spending more time paging than executing

Performance problem caused by thrashing (Assume global replacement is used)

- processes queued for I/O to swap (page fault)

- low CPU utilization

- OS increases the degree of multiprogramming

- new processes take frames from old processes

- more page faults and thus more I/O

- CPU utilization drops even further

To prevent thrashing, must provide enough frames for each process: Working-set model, Page-fault frequency

Working-Set Model

- Locality: a set of pages that are actively used together

- Locality model: as a process executes, it moves from locality to locality

- program structure (subroutine, loop, stack)

- data structure (array, table)

- Working-set model (based on locality model)

- working-set window: a parameter $\Delta$ (delta)

- working set: set of pages in most recent $\Delta$ page references (an approximation locality)

Prevent thrashing using the working-set size

- $WSS_i$ : working-set size for process i

- D = $\Sigma WSS_i$ (total demand frames)

- If D > m (available frames) -> thrashing

- The OS monitors the $WSS_i$ of each process and allocates to the process enough frames

- if D « m, increase degree of MP (multiprogramming)

- if D > m, suspend a process

Pros:

- prevent thrashing while keeping the degree of multiprogramming as high as possible

- optimize CPU utilization

Cons:

- too expensive for tracking

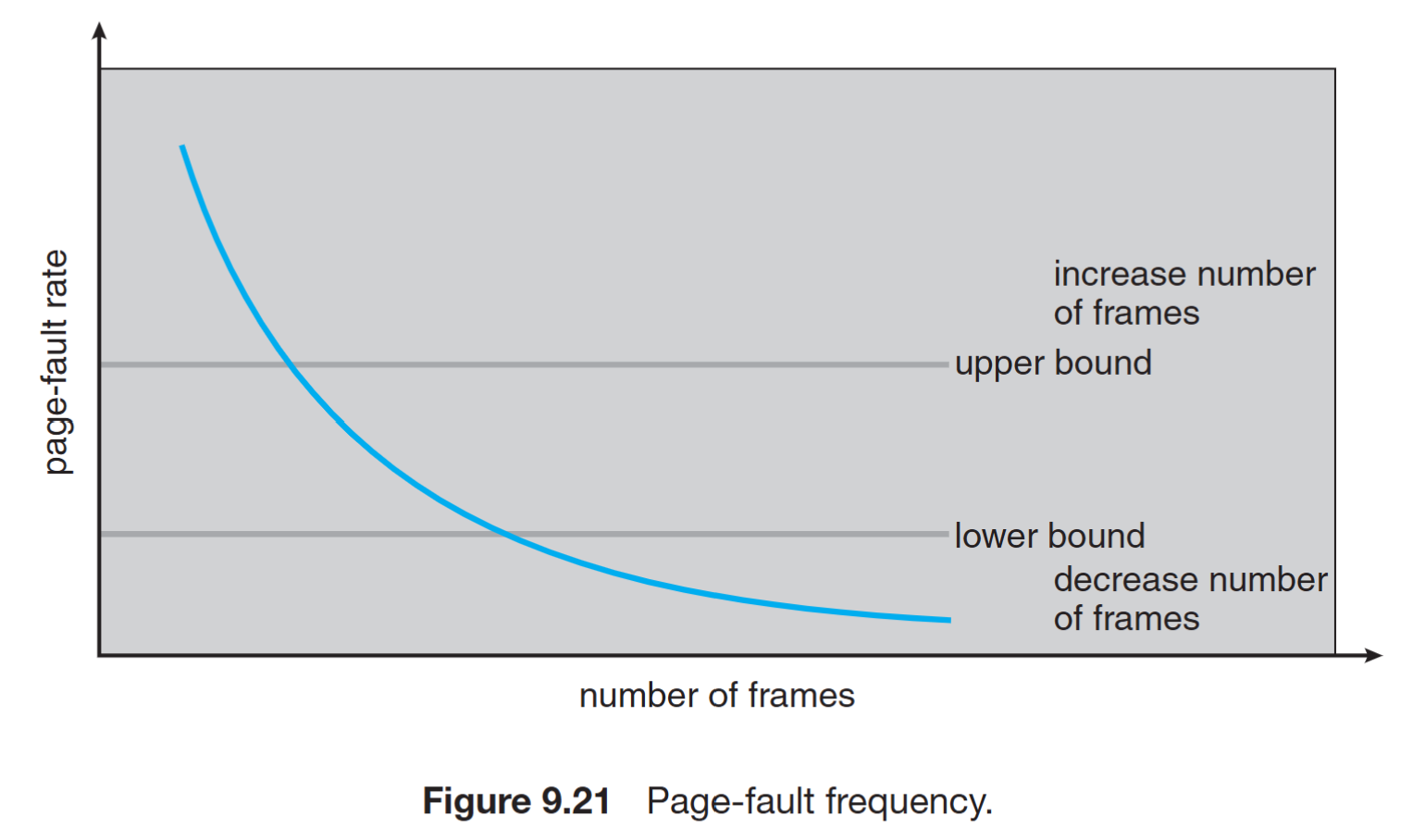

Page-Fault Frequency Scheme

Page fault frequency directly measures and controls the page-fault rate to prevent thrashing

- Establish upper and lower bounds on the desired page-fault rate of a process

- If page fault rate exceeds the upper limit: allocate another frame to the process

- If page fault rate falls below the lower limit: remove a frame from the process